Building the Basics for School

Introduction:

According to the National Center of Education Statistics, in 2018, 1.4 million kids entered the public-school system as preschoolers and 3.6 million children were enrolled as kindergarteners (NCES). Early childhood education is extremely important in creating a firm foundation for future life in children. Research shows that those children who had preschool experience performed much better and with greater academic skill than their peers when evaluated in seven years and ten years (Campbell). The research also goes on to say that introduction to mathematics and reading during this developmental period was much more effective then introducing those subjects later in school (Campbell). While these short-term results are already very appealing, the long-term results of having an effective childhood education are just as good, if not even better. People who had success in early academic educations earned more at their jobs, were less likely to participate in criminal activities, and were less likely to be pregnant while still a teenager (Hartman).

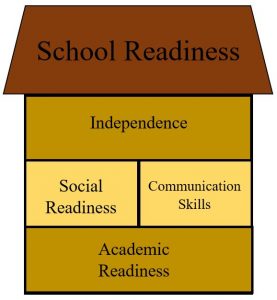

While school is great for fostering knowledge and teaching new skills to children, there are certainly ways that parents can help and assist their children in getting a solid foundation that they can use to build upon in later years of education and even life. School readiness is defined as academic knowledge, independence, communication, and social skills children need to do well in school (NEA). Additionally, another article defines school readiness as a multidimensional construct, encompassing not only academic skills but also social-emotional development and physical health (Ferretti). School readiness does not come naturally or easily to children and requires an active effort from parents to work effectively. This program focuses on four key areas that the National Education Association has identified as vital in preparation of a child for school. They are academic readiness, social readiness, independence, and communication skills.

Review of Literature:

- Academic Readiness:

Academic readiness is the child’s basic knowledge of themselves, their family, and the world around them (NEA). This area is important because these basic skills are what the teachers are going to rely on and build from when the child enters school. Research says that the parents view of academic readiness is not dependent on the parents’ race, poverty status, or level of education (Puccioni). One factor that does play a role in academic readiness is the employment status of the parents. While all parents express some sort of concern for their child’s school readiness, unemployed parents tend to neglect or place a low emphasis on their child’s academic readiness while employed parents view it as an important factor in their child’s future success and thus pay more attention to it (Puccioni). The same research also found that the parents have a positive view on their child’s school readiness when the child can name shapes, numbers, and letters. Most parents do not think about the child’s ability to reason or think complex ideas or thoughts at this age. A positive correlation was also found in that the parents who stressed mathematical and general knowledge during the school preparation period had kids with a greater knowledge of numbers, letters, and words than their peers.

Promoting creativity in early childhood is also part of academic readiness. Many projects for children are based on the final product and not the process of getting there. Projects and activities that only really care about the end-product are called product art (Richards). What parents and educators need to promote is process art. Process art focuses on the creating, not what is created (Richards). Richards claims that process art is much more developmentally appropriate for children than product art. Process art fits in with play because children have the ability and opportunity to create what they want and with whatever they want. We as adults like to see a pretty classroom of hand-print turkeys for Thanksgiving or twenty-three Christmas trees neatly placed in a row but that does not help children in developing a creative mind and creating something of their own even if it looks like complete gibberish and a mess to us, adults. Not only does process art facilitate creativity, it also builds autonomy and independence since each child is creating a unique project with its own complications and challenges (Richards).

Routines are also positively associated with desired childhood outcomes such as health, results in school, and control of emotions. In her research, Larissa Ferretti defines family routines as observable, repetitive behaviors that involve two or more family members and occur with predictable regularity in the day-to-day and week-to-week life of the family (Ferretti). Research shows that preschoolers who had routines were predicted to be more developed cognitively, have a more diverse vocabulary, and have better literacy skills than their peers (Ferretti). Additionally, established routines in early childhood help children adjust to the cycle of school and lead to less behavioral and emotional problems when compared to peers without routines (Ferretti).

However, routines have benefits when the child is participating in them. For example, if a family has their dinner at five P.M. sharp every evening, while that is a routine, it is not all that beneficial for the child if they just come and eat and do nothing else. The point of routines is to get the child involved and invested in making the routine work. For example, while the mother is taking the spaghetti out of the oven, the child can get the get the forks and napkins for the family. Not only is it making the child an active participant, it is also working on counting on how much forks are needed and social skills of talking with the mother. Also, during the actual dinner, the parents should take time to talk the child and make the child also an active part of there conversation. This will also help solidify and cement the routine while also building much needed social skills within the child.

- Social Readiness:

Social readiness is also an important area in early childhood education. While academic smarts such as knowing letters and numbers are very important, other skills such as sharing, considering feelings of others, saying “thanks”, and controlling frustration are just as important. Social competence is defined as the ability to achieve personal goals in social interaction, while simultaneously maintaining positive relationships with others over time and across situations (Kemple).

Children need a positive self-identity, which is the sense of worth and personal power. It can be fostered by giving them some room in choosing activities and giving ample time to complete them (Kemple). Interpersonal skills or the ability to make friends and understand social situations is also important. This can be encouraged by telling children to express their feelings to their friends and classmates (Kemple). Another key area in social readiness is cultural competence, which is the ability for children to accept others who are different from them in race or beliefs and recognize unfair treatment of those people. This element can be practiced by giving children scenarios and asking them to find solutions or alternative ways to make the scenarios fair and just (Kemple). Emotional intelligence, or the ability to empathize with others and label and manage emotions of others and themselves, is also very important in preparation for school and can be strengthened by reminding children to breath in deeply to clam down when angry or count to ten (Kemple). Another important part of social competence is social values, which are helpfulness, truthfulness, and concern for others. These can be nourished in children by giving them responsibilities and praising them when they do a good job (Kemple). The last part of social competence is self-regulation. Self-regulation is extremely important because it helps children control emotions and resist temptations from peer-pressure. Examples of promoting self-regulation is using a timer for watching television or playing electronic games and being able to wait patiently for their turn in something (Kemple).

- Independence:

Children need to have some sort of self-care and self-management before they enter school. The basic skills such as going to the restroom, putting on their shoes, and being able to spend time alone without their parents need to be mastered before children enter the education system. One way to build these independence and self-care skills in children is to allow for risky play.

Risky play is defined as a thrilling and exciting activity that includes some risk of injury (McFarland). Risky play allows children to learn to make their own decisions and figure out what capabilities they have through successes and failures. These successes and failures can also be an important source of motivation for children in pushing them to reach new goals and surpass challenges. (McFarland). Risky play has many benefits mentally for the child, such as pride, excitement, and fun, but also has many physical benefits, such as optimizing balance, building strength, and refining motor skills (McFarland). In early childhood education, risky play has shown to produced children with a strong sense of education.

Even though there are clear benefits to risky play, parents and educators should still take caution and supervise the children under their care. We all know that these days people will sue for just about anything and trying to keep the children safe and ourselves out of legal trouble by forbidding any risky play seems like a logical move. However, this is detrimental to the development of the children. One way to combat this is for parents and guardians to assess the capabilities of the child and be supportive while balancing the risk of injury in an activity with the benefits of that activity. For example, if a parent sees bicycles as dangerous equipment for play, then the child has a much less chance of doing physical activities and exercising. However, if the parents recognize that there is a potential for the child falling and maybe hurting themselves but also realize that the benefits of an active lifestyle and exercise from bicycle riding outweigh the inactive lifestyle from supposedly protecting the child and forbidding bicycle riding, they can use training wheels or even holding their child while they learn to minimize and balance those risks while reaping the benefits from the activity. The same logic can be applied to any physical activity such as climbing the monkey bars or even running around during tag. A parent’s job is to remove the dangers and hazards that the child does not see or recognize and not to remove the risk from their play (McFarland).

- Communication Skills:

Children need to have the ability to express what they want and think which is where communication skills come in very handy. It is through speaking that the child will learn about new places and things. Speaking is also the basis of later writing and reading skills which means that it is very important to build a strong foundation in communication skills (NEA). In a study done on preschoolers it was found that as active communication skills increase, so does social cooperation and interaction (Atabey).

Active listening is the basis of good communication skills (Atabey). We as adults understand that we need to be nice and considerate of others opinion even if we do not necessarily agree. Children do not have these basic concepts ingrained in their brains and can sometimes come off as brash and even rude when they are just speaking what is on their mind. Therefore, it is important to teach children how to properly engage in civil discussion and how to make their ideas heard while simultaneously thinking and hearing out the opinions of their fellow classmates and peers. To effectively engage in active listening, children need to be taught about their body-language, tone of voice whenever they are talking, and posture (Atabey). These are all part of non-verbal communication which is just as important as the verbal part of the conversation. When communication skills become natural in children, they are more likely to make friends, wait their turn, use polite words, and generally have a higher level of social interaction (Atabey).

Purpose of Prevention Program:

The purpose behind this program is to educate parents and guardians on how to prepare children for school. This program focuses on four key areas that all combine to form the concept of school readiness. These four areas are academic preparedness, independence, social readiness, and communication skills. This program is designed with minimal teacher or instructor guidance but rather focuses on children fueling their own education and learning through creative activities that they control heavily. The end goal is to have children with basics cemented at their core. This will allow for future learning and higher academic achievement.

Theoretical Model:

As a conceptual illustration of this program, I decided to use a house and named the program “Building the Basics for School”. The reason for using a house as a model was because one can build a house with as little material as possible but that will compromise the stability and soundness of the structure. Same thing with school readiness. One can skip a key area and have a smart child who knows all his letters and numbers can make friends with just about anyone, but as soon as his mother or father are out of sight, he becomes anxious and starts crying because he was never given an opportunity to develop a sense of self-power and independence.

Program Activities:

While most of these activities cross over somewhat, I decided to split them up to address a key area I was focusing on.

- Academic Readiness:

The activity for academic readiness is based on exploring the creativity of the children and letting them strengthen their artistic skills. For this activity, the children will be divided into groups of three or four peers and given a blank white poster with crayons or coloring pencils. Each child will also pick a random letter of the alphabet form a hat. The children will then have ten minutes to talk together and together draw something or a few “somethings”. Each child can only draw images that begin with the letter they have previously drawn. After the ten minutes are up, the groups will present their drawings to the rest of their peers and explain or tell a story about what they drew or what it was supposed to be.

As mentioned above, the primary focus of this activity is to instill creativity in the students. Research does confirm that children like to be creative and draw things at this age (3-4 Years: Preschooler Development). Fortunately, there are also beneficial unintended results form this activity. This activity also promotes sharing of the poster and crayons or colored pencils. Its also requires the kids to communicate with one another and talk about what they are drawing since they can only draw items that start with the letter they have chosen. Also, some communication skills are being worked on and developed since they must also present the poster and explain what they drew or what they were trying to draw. Another benefit from this activity is that it will help establish a routine for the children because this activity will be the first thing they do each day. This project would also be classified as process art because the children will have a free rein to draw and create whatever they please with the end-product mattering not as much as the actual process.

- Social Readiness and Communication Skills:

I decided to combine social readiness and communication skills and have one activity for both since they are extremely closely tied together.

In this activity, the children will be split up in to small groups of three to four kids per group with each group being headed by an adult. Each adult will have a children’s book with pictures that one of the children from that group has chosen or brought from home. The child choosing will be different each time this activity is implemented to ensure fairness. The purpose will be for each child to tell the group what the characters in the book are feeling based on what they see in the pictures. That part will build and fortify the labeling and identification of emotions. Each child will go in order and present their own opinion of what emotions are being displayed and how each character feels while the other participants will be listening and gauging their own responses with what is being said. This is the listening part of communication skills. Afterwards, the children will decide on how the emotions, if negative, can be fixed and resolved. This will work on the management and control of emotions and problem solving as a group. Finally, the teacher will guide the kids on how this kind of “what will make them happy?” thought process can be implemented in each child’s daily life.

- Independence:

There is not a specific activity that I want to introduce here but rather I want to encourage parents and guardians to allow children to play these “risky” games such as tag and red rover. I especially like red rover as an activity for elementary school kids and kids younger than because it builds many core skills children need in life and for education. Red rover is a game that involves two teams. Each team lines up and each teammate holds hands so that in the end there are two lines of kids facing each other. Then each team takes turns choosing one person form the other team to try and break through their own team’s line. If the person chosen breaks through, then they take one person back with them to their team and if they do not break through, then they join the opposing team. The goal of the game is for one team to acquire all the people. Also, this game allows everyone to be on the winning team at the end since the game ends when one team has completely joined the other.

While some may say that the game is far too dangerous for children, I believe, and research confirms, that with proper supervision there are many benefits to it. First, the game builds teamwork since everyone on one team is holding hands and all have one goal in mind. Also, the game builds independence and self-awareness of each child. If a smaller or weaker child is chosen, the child must decide which pair of hands on the opposing team will be breakable and weak enough for them to charge through. Each team also must make a collective decision on who they want to choose. If they choose a stronger peer, they may be able to weaken the other team and upgrade their own if they stop them, but also the stronger peer has a much higher chance of breaking through. If the team chooses someone weaker, they can stop them more easily but would also have a weaker line afterwards. Not only are there cognitive and decision building benefits but also physical benefits. Red rover is a running game which means that the children will also get a fun form of exercise, promoting physical development while subconsciously furthering their social, cognitive, and independent development.

Evaluation Measure:

This evaluation was created by choosing two questions out of each key area of school readiness. The last two questions are supposed to gauge the attitude of the parent and see if they do notice a change in their child’s behavior. These questions where designed in a way that a parent with a child well prepared for school should be answering mostly options D or E and maybe a few C’s occasionally. A parent with a child that is unprepared for school will be mostly answering B’s and A’s.

- Can your child recognize their name, family, and other close relatives?

- None

- Their name

- Immediate family (father, mother, brother, sister)

- Extended family (grandfather, grandmother, close family friends)

- All three

- Does your child know colors, letters of the alphabet, and numbers?

- None

- Colors

- Letters

- Numbers

- All three

- Does your child regularly start hitting, screaming, or biting when frustrated?

- Never

- Rarely

- Sometimes

- Always

- How likely is your child to play with other kids his/her age?

- Not likely

- Rarely

- Likely

- Very likely

- How confident are you in your child’s ability to dress themselves and use the bathroom?

- Not confident at all

- They need some assistance

- They can mostly handle themselves

- Very confident

- How good is your child at following directions, cleaning up toys after himself, and doing simple chores?

- They are their own authority

- Will listen for reward

- mostly obedient

- Can take care of themselves and follow directions

- Do you talk, sing, and answer your child’s questions on a regular basis?

- Never

- Rarely

- Usually

- All the time

- Does your child respect others opinion and to listen to what others have to say?

- Only own opinion matters

- Recognizes others have opinions too

- Considers opinions of others

- Respects ideas of others even if they do not agree

- Do you feel that this program helped you understand what your child needs for school?

- Yes

- No

- Did this program help your child become more prepared to enter school?

- Yes

- No

Sources:

Works Cited:

“3-4 Years: Preschooler Development.” Raising Children Network, 17 Nov. 2017, raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/development/development-tracker/3-4-years.

“5-6 Years: Child Development.” Raising Children Network, 16 Nov. 2017, raisingchildren.net.au/school-age/development/development-tracker/5-6-years.

Atabey, Derya. “Okul Öncesi Dönem Çocuklarının Etkili İletişim ve Sosyal Becerileri Üzerine Bir Çalışma.” Inonu University Journal of the Faculty of Education (INUJFE), vol. 19, no. 1, May 2018, pp. 185–199. EBSCOhost, doi:10.17679/inuefd.323598.

Campbell, Frances A., et al. “Early Childhood Education: Young Adult Outcomes From the Abecedarian Project.” Applied Developmental Science, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2002, pp. 42–57. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0601_05.

Ferretti, Larissa K., and Kristen L. Bub. “Family Routines and School Readiness During the Transition to Kindergarten.” Early Education & Development, vol. 28, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 59–77. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/10409289.2016.1195671.

Hartman, Suzanne, et al. “Behavior Concerns Among Low-Income, Ethnically and Linguistically Diverse Children in Child Care: Importance for School Readiness and Kindergarten Achievement.” Early Education & Development, vol. 28, no. 3, Apr. 2017, pp. 255–273. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/10409289.2016.1222121.

Kemple, Kristen. “Social Studies, Social Competence and Citizenship in Early Childhood Education: Developmental Principles Guide Appropriate Practice.” Early Childhood Education Journal, vol. 45, no. 5, Sept. 2017, pp. 621–627. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s10643-016-0812-z.

McFarland, Laura, and Shelby Gull Laird. “Parents’ and Early Childhood Educators’ Attitudes and Practices in Relation to Children’s Outdoor Risky Play.” Early Childhood Education Journal, vol. 46, no. 2, Mar. 2018, pp. 159–168. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s10643-017-0856-8.

“Preparing Your Child for School.” NEA, www.nea.org/home/59838.htm.

Puccioni, Jaime. “Parents’ Conceptions of School Readiness, Transition Practices, and Children’s Academic Achievement Trajectories.” Journal of Educational Research, vol. 108, no. 2, Mar. 2015, pp. 130–147. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/00220671.2013.850399.

Richards, Elizabeth. “Handprint Turkeys, Step Aside: Embracing Process Art in Early Childhood Programs.” Exchange (19460406), no. 244, Nov. 2018, pp. 52–55. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=132934973&site=ehost-live.

“The NCES Fast Facts Tool Provides Quick Answers to Many Education Questions (National Center for Education Statistics).” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a Part of the U.S. Department of Education, nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372.

Link to Original Paper: Building the Basics for School